Has the gas price shock already triggered demand destruction? And where will gas prices go from here?

Following skyrocketing gasoline prices, the question arises as to when demand destruction will set in, where people will start to drive less, take more time to save gas when driving or begin to favor the most economical vehicle in their garage. If enough people do, demand begins to decline and gas stations have to compete for dwindling business. The destruction of demand is what would cause the price to drop further. Are we already there?

The Department of Energy’s EIA measures gasoline consumption in terms of barrels supplied to market by refiners, blenders, etc., not in terms of retail sales at gas stations. The volume of gasoline delivered fell for the third consecutive week. This is unusual at this time of year when gas mileage normally increases during the summer.

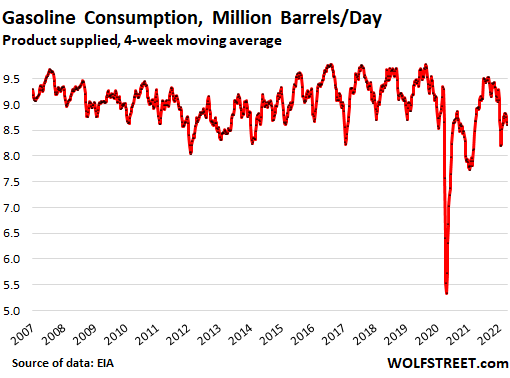

The EIA reported on Thursday that gasoline consumption fell to 8.61 million barrels per day in the week ended April 8 based on a four-week moving average (red line), the highest low since March 4, down 2.3% from the same period in 2021 (black line) and down 8.1% from the same period in 2019 (grey line).

Consumers began to react in January.

Note how the last 11 months (red line) followed very closely the pre-Covid period three years earlier (grey line) until they started to diverge sharply, not only in March, but already in mid -January, and have been solidly below the 2019 level ever since.

Gasoline prices began to soar from crashed levels in April 2020. In May 2021, the average price of gasoline across all grades exceeded $3.00 per gallon, a multi-year high, and continued. In November 2021, it reached $3.40 per gallon and paused. Then in early February, it started to skyrocket and hit $4.32 on March 14.

But since mid-March, the price has come down. Now at $4.09, it’s still a nosebleed high but is a bit lower than it was:

Gas stations don’t lower prices out of the goodness of their hearts. They lower prices because sales are affected and price competition has developed between service stations in an effort to maintain sales volume. And gas stations could lower their selling price without hurting their profit margins, because the costs of their product have also fallen.

The destruction of demand affecting gasoline would then be passed on to demand for crude oil. But crude oil has uses far wider than just gasoline, including the burgeoning petrochemical industry. And a slight drop in U.S. gasoline demand isn’t going to shake global crude oil markets too much.

The price of crude oil has already rebounded again.

WTI crude had climbed to $130 a barrel, then fell back into the $90 range. In recent days, it has changed course again and is now at $106. This is not a good sign for the price of gasoline.

Obviously, there has been some demand destruction, and that may have been enough to bring the price of gasoline down a bit.

But maybe not. Perhaps this destruction of demand was not the cause of the drop in gasoline prices. Maybe they fell for another reason, like the current volatility that has affected everything. The wild dynamics of the commodity markets ensure this.

My guess: gas prices will rise further.

I can see the demand destruction, but right now I doubt it’s large enough to cause a sustained drop in the price of gasoline. I wouldn’t be surprised if the price goes up again. Crude oil prices have already started to climb again. It could be a long process with very volatile and zigzagging prices higher and higher. That’s my guess.

What we know.

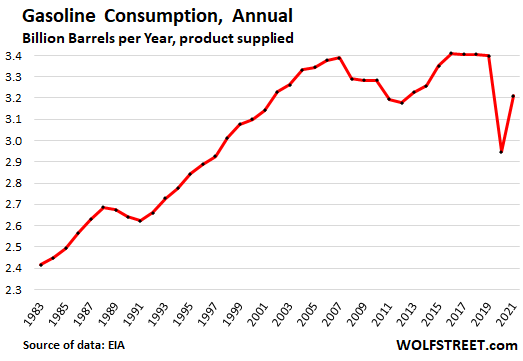

Annual gasoline consumption peaked in 2007 then declined over the next five years to 2012 by a total of 6.3%. It then rose again and reached that 2007 peak again in 2016, then again in 2017, and in 2018, and again in 2019, without exceeding it. And then in 2020, consumption collapsed. In 2021, consumption has recovered markedly, but total annual consumption still ends the year down 5.3% compared to 2007!

But the total number of kilometers traveled by vehicles hits a record every year from 2015 to 2019. And in 2021, despite the slump in 2020, miles driven increased 6.6% from 2007. People are driving more, but they’re using less gas to do so:

So there are many other factors that play into gas mileage, not just the price. This includes long-term technology trends, such as more fuel-efficient vehicles and the arrival of electric vehicles on a scale now large enough to reduce gas mileage.

Other changes are also impacting gas mileage, some dating back more than a decade, such as the boom in high-rise residential construction in urban centers that has reduced or eliminated fuel consumption. car travel for residents; or the tendency to work from home at least part of the time, which also reduces commuting miles.

The increase in driving holidays during the pandemic has pulled in the opposite direction, which may now have been replaced by flying (domestic leisure traffic is on the rise).

Gasoline consumption is also highly seasonal, making it even more difficult to spot where demand destruction has occurred due to price and where unusual seasonal patterns might be at play.

Do you like to read WOLF STREET and want to support it? You use ad blockers – I completely understand why – but you want to support the site? You can donate. I greatly appreciate it. Click on the mug of beer and iced tea to find out how:

Would you like to be notified by e-mail when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Register here.